|

|

Death by suicide is the most personal act any person can make, involving a wide circle

of people — the survivors. The following is intended to help survivors along the path following a bereavement by suicide —

to help you under-stand what is happening to you. You have found yourself experiencing emotions that are unfamiliar, unexpected and frightening —

almost beyond your control. Bereavement by suicide is very different from any other bereavement, giving rise to all the emotions following any

loss, alongside many other emotions. Since

the death is self-chosen and self-inflicted, there are the unanswered and unanswerable questions of why? and, some-times,

how? and also if only? and what if? In the following we hope to outline the emotions you may experience, but it is important to remember

that: The process is unique to you.

The emotions experienced are a natural part of the journey you will make. You are the only person who knows how you feel.

Feelings

Initially, there are feelings

of shock and disbelief which last longer than with other bereavements. This leaves survivors feeling numb and empty of emotion,

often finding difficulty in accepting the reality of the death — "This can't be happening to me."

There may be a feeling of disorientation; the real world is

going on all around, but the survivor is not part of it. The survivor is just an onlooker — separate and alone. Many survivors experience

suicidal thoughts — of wanting to join the deceased and escape from the present confusion

and nightmares. Symptoms

The shock of any sudden death gives rise

to real physical and emotional symptoms. These may include:

Tightness in the chest

Hollow feelings in the stomach

Breathlessness

Lack of concentration

Exhaustion

Lethargy

Physical pain

These feelings act as a 'cushion', to enable the survivor to cope with this terrible situation in which they find

themselves.

Looking for a reason for the decision is inevitable. Guilt

Guilt is often an overriding

emotion, survivors feeling in some way responsible for the death, and that the death was somehow preventable. The "if

onlys" and "what ifs" come to mind over and over again:

'Could we have pre-vented this?"

"Did we actually

contribute towards it?"

'We should have seen the signs"

"We are to blame!" But if help was not sought, or signs not shown, how could survivors have known?

As well as self-blame, there is often a tendency to blame others, frequently within the

close family, leading to a breakdown in communications. Members of the medical profession, the police, God and church friends,

work, social circumstances —these are all targets for blame. Blaming is often a way of dealing with grief, giving only

temporary relief and causing damage to relationships within family and friends — just at a time when support is needed.

Searching

Looking for a reason for the decision is inevitable. Trying to understand can occupy the

mind for long periods. However, the answer will never be known, since the only informant is no longer with us.

Anger

Anger is a normal part of grieving — especially so following a suicide. The anger

needs to be acknowledged and expressed; it is realistic and must not be suppressed out of a sense of loyalty to the deceased.

It is important to realise that the deceased can be loved, but the action they have taken can cause anger. The anger may be

directed to others, leading to blame.

Anger is sometimes unacknowledged because of its connection with the feelings of guilt. These swings

of emotions —from anger to guilt, to blame, to anger — may give rise to feelings of a loss of control —

"going mad" and being different, and noticeably so. Rejection

An overwhelming emotion,

since the loved one has chosen to go, can be rejection, that those left behind were not worth living for, and perhaps not

even given the opportunity to be of help. Feelings of unworthiness may lead to feelings of being unloved, and hence unlovable.

This sense of rejection, if not questioned, may lead to insecurity and a sense of failure.

Following bereavement by suicide,

the survivor may be left feeling vulnerable, wondering what will happen next, distrusting everything and everybody. This may

lead to a loss of self-esteem and confidence, a fear of being let down, and sensitivity to any rejection, however small. Relief

It may be difficult to admit to relief, but when depression, despair and unsuccessful

suicide attempts have been experienced by family and friends, there may be relief following the final successful attempt,

coupled, of course, with sadness. The deceased is no longer in despair, and the constant threat of suicide is over.

Shame

A stigma attached to suicide is still present in our society, and may give rise to

a feel-ing of being judged and found wanting. Also, the loved one may be judged as cow-ardly or selfish. Society in general

has difficulty in dealing with suicide, and will take many and varied efforts to avoid it. This leads to isolation —

survivors feel they are alone with no opportunity to speak of the loved one.

Depression

Depression is almost inevitable following a bereavement by suicide. The constant swings of emotions questioning,

physical pain and lack of sleep — will have an effect. It may be necessary to consult a doctor.

Effects on the

family

Communication may be difficult because of family members'

fear of hurting one another by speaking of the suicide, or perhaps there may be blame within the family.

Each member will be

affected in a different way, since each bore a different relationship to the deceased. The differences need to be discussed. accepted and respected,

as each member will grieve in their own way and in their own time. Be kind to yourself: It is so important to understand

that all the feelings mentioned are normal and to be expected, in varying degrees and at different times.

No one can give a pattern for grief — it is different for all of us.

Let the emotions be felt and do not attempt to fight them. Allow yourself to be sad, angry, guilty — do not

let anyone else tell you how you should, or ought to feel. You have experienced a traumatic and terrible shock.

Give yourself time to heal.

Events will trigger emotions unexpectedly, but allow

for this and do not be ashamed. You will never 'get over it', but, in time, will learn to live with it.

Life will never be the same again, never back to 'normal', but you can create a new normal.

Survival guide

The survivor of a suicide bereavement faces a stark choice:

It

is up to you to decide whether to be permanently hurt by the last act of a free individual or not ... This option is YOURS."

(Lake, 1984)

Know you can survive. You may not think so, but you can.

Struggle with 'why' it happened until you no longer need to know why' or until you are satisfied with partial answers.

Know you may feel overwhelmed by the intensity of your feelings, but all these feelings

are normal.

You may feel rejected and abandoned — share these feelings.

Anger, guilt, confusion, denial and forgetfulness are common responses. You are not going crazy; you are in mourning.

Be aware you may feel anger at the person, at the world, at friends, at God, at yourself: it's all right to express it.

You may feel guilty for what you think you did or did not do. Remember the choice was not yours — one cannot

he responsible for another's actions.

Find a good listener: be open and honest about

your feelings.

Do not remain silent about what has happened, about how you feel.

You may feel suicidal. This is normal; it does not mean you will act on those thoughts.

Do not be afraid to cry. Tears are healing.

Remember to take one moment or day

at a time.

Keeping an emotional diary is useful as well as healing. Record your

thoughts, feelings and behavior. Writing a letter to the deceased expressing your thoughts and feelings can also be part of

the healing process.

Give yourself time to heal.

Expect

setbacks. If emotions return like a tidal wave, you may be experiencing unfinished business'.

Try to put off making major decisions.

Seek professional help if needed. Be

aware of the pain of your family and friends.

Be patient with yourself and with others

who may not understand.

Set your own limits and learn to say no.

Call on your personal faith to help you through.

Some survivors struggle with

what to tell other people. Although you should make whatever decision feels right to you, most survivors have found

it best to simply acknowledge that their loved ones died by suicide.

You may find that

it helps to reach out to family and friends. Because some people may not know what to say, you may need to take the

initiative to talk about the suicide, share your feelings, and ask for their help.

Even

though it may seem difficult, maintaining contact with other people is especially important during the stress-filled months

after a loved one's suicide.

Keep in mind that each person grieves in his or her own

way. Some people visit the cemetery weekly; others find it too painful to go at all.

Each

person also grieves at his or her own pace; there is no set rhythm or timeline to healing.

Anniversaries, birthdays, and

holidays may be especially difficult, so you might want to think about whether to continue old traditions or create some new

ones. You may also experience unexpected waves of sadness; these are a normal part of the grieving process.

Try to take care of your own well-being; consider visiting your doctor for a check-up.

Many survivors use the

arts to help them heal, by keeping a journal, or writing poetry or music.

Be kind

to yourself. When you feel ready, begin to go on with your life. Eventually starting to enjoy life again is not

a betrayal of your loves one, but rather a sign that you've begun to heal.

It is common

to experience physical symptoms to your grief: headaches, sleeplessness, loss of appetite, etc.

Ask the questions. Work through the guilt, anger, bitterness and other feelings until you can let them go. Letting

go does not mean forgetting.

Know that you will never be the same again, but you can

survive and go beyond just surviving.

Recognize you are not alone — many others

share this type of loss. If there is a group in your area where other survivors of suicide bereavement meet, then go along

and meet them. You have nothing to lose and perhaps there is much to be gained. Those who are left behind after a suicide

can be helped by talking to others who have experienced the same thing.

|

|

|

|

|

Before us they have gone, leaving us with the pain of loss. They have not left us

but grown wings so that they might fly from all that caged them here. Springing from their cocoons of pain they

soar on to heaven. Yet they are with us still, shining the beauty of their butterfly wings upon our souls. Softly,

so softly, we feel them flutter upon the breeze gently soothing our hearts. Silently they call to us and say, We are

here and we love you so. We are with you forever. Now we live in peace and joy. Now we are free."

Healing...

In the Aftermath of a Suicide. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Nothing is as hard to understand as when someone makes

the decision to stop living. While the pain and suffering of the person who dies by suicide has ended, it has increased many

times over for those who grieve the death. Those who greive are often referred to as survivors. Whether

you are grieving the death by suicide of a relative or friend, or know someone who is a survivor, the following information

is important.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Upon hearing of the suicidal death of a relative or friend,

many survivors report feeling numb and confused, almost like everything had just been turned upside down and inside out. Over the next few hours, days, weeks and months, they experienced other feelings such as intense

anger, disorientation, rage, fear, guilt and anxiety. Loss of appetite, sleep disturbances and periods of "unreality" are

common. There can be periods

when survivors blame themsleves or others for the suicide. For the most part, these experiences are very normal reactions

to an abnormal event. While it is normal to blame oneself or others, it is important to recognize that neither you nor others

are at fault. The person who died by suicide made the decision to do so. If you are supporting

someone else who is grieving a suicidal death, keep the following in mind. Give lots of support

to those who are grieving a suicidal death, as you would those who grieve death by other causes.

Be available to listen. Often those bereaved need to discuss the suicidal

death. Recognize that they will struggle with the question of "WHY" for a long time. Do not offer ready made or pat answers

in order to alleviate their feelings. The do not help in the short or long term.

Recognize that those who are bereaved may display intense feelings of anger, guilt, anguish, fear, sadness, etc.

You cannot, and should not, make these feelings go away. Think of it as a storm. It will become quite turbulent, but with

lots of support people ride out their feelings. Attempting to block or avoid these feelings keeps people from moving out of

the storm as soon as they might otherwise.

Do

not offer alcohol or drugs as a means of reducing their grief. They numb feelings which need to be expressed, and complicate

the grieving process.

Recognize your own feelings.

In supporting others you will also need someone to talk to about your feelings.

Individuals who are grieving any death need support after the initial aftermath of the death. Many survivors report

that generally friends and relatives were great during the time around the funeral, but stopped coming around after a few

months. Sometimes, this can be taken as evidence that you do, in fact, blame them for the suicide. Apart from the intense

emotional times during the funeral, there can be periods which are particularly difficult over the next few years (i.e. birthdays,

anniversary of death, etc.).

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The following suggestions are directed towards survivors

and are provided by Iris Bolton, author of My Son... My Son... A Guide to Healing after Death. Loss and Suicide. Know you can survive. You may not think so, but you can.

Stuggle with "why" it happened until you

no longer need to know "why", or until you are satisfied with partial answers.

Know you may feel overwhelmed by the intensity of the feelings, but all your feelings will be normal.

Anger, guilt, confusion, forgetfulness are common responses. You are not

crazy - you are in mourning.

Be aware you may

feel appropriate anger at the person, at the world, at God, at yourself.

You may feel guilty for what you think you did or did not do.

Having suicidal thoughts is common. It does not mean you will act on these thoughts.

Remember to take one moment or day at a time.

Find a good listener with whom to share. Call someone.

Don't be afraid to cry. Tears are healing.

Give yourself time to heal.

Remember, the choice was not yours. No

one is the sole influence in another's life.

Expect

setbacks, Don't panic if emotions return like a tidal wave. You may only be experiencing a remnant of grief.

Try to put off major decisions.

Give yourself permission to get professional help.

Be aware of the pain of your family and friends.

Be patient with yourself and with others.

Set

your own limits and learn to say no.

Steer

clear of people who want to tell you what or how to feel.

Know that there are support groups that can be helpful, such as Compassionate Friends, or Survivor of Suicide Groups.

If not, ask a professional to help start one.

Call

on your personal faith to help you through.

It

is common to experience physical reactions to your grief, i.e. headaches, loss of appetite, inability to sleep, etc.

The willingness to laugh with others and at yourself is healing.

Wear out your questions, anger, guilt, or other feelings until you can

let go of them.

Know that you

will never be the same again, but you can survive and go beyond just surviving...

The Journey Through Grief

by Alan D. Wolfelt, Ph.D. The death of a loved one changes our lives. Moving from "before" to "after" almost always is a long,

painful journey. But if we are to heal, we cannot avoid our grief. We must journey through it all, sometimes meandering the

side roads and plowing directly into its raw center. The journey also requires mourning. That’s different from grief. Grief is what you think and feel "inside."

Mourning is the outward expression of those thoughts and feelings. To mourn is to be an active participant in our grief journeys.

We all grieve when someone we love dies, but if we are to heal, we must also mourn. There are six "yield signs" you are likely to encounter along the journey through grief - the "reconciliation

needs of mourning." Need 1 - Acknowledging the reality of the death The first need of mourning involves gently confronting the reality that someone you care about will

never physically come back into your life again. Whether the death was sudden or anticipated, acknowledging the full reality of the loss may occur

over weeks and months. To survive, you may try to push away the reality of the death at times. You may discover yourself replaying

events surrounding the death and confronting memories, both good and bad. This replay is a vital part of the need for mourning.

It’s as if each time you talk it out, the event is a little more real. Remember - this first need of mourning, like the other five

that follow, may intermittently require your attention for months. Be patient and compassionate with yourself as you work

on each of them. Need 2 - Embracing the pain of loss This need of mourning requires us to embrace the pain of our loss - something we naturally don’t want to do.

It is easier to avoid, repress or deny the pain of grief than it is to confront it. Yet it is in confronting our pain that

we learn to reconcile ourselves with it. You

will probably discover you need to "dose" yourself in embracing your pain. In other worse, you cannot (nor should you try

to) overload yourself with the hurt all at one time. Sometimes you may need to distract yourself from the pain of death, while

at other times, you will need to create a safe place to move toward it. Unfortunately, our culture tends to encourage the denial of pain. If you openly express your feelings

of grief, misinformed friends may advise you to "carry on" or "keep your chin up." If, on the other hand, you seem to remain

strong and in control, you may be congratulated for "doing well" with your grief. Actually, doing well with your grief means

becoming well-acquainted with your pain. Need 3 - Remembering the person who died Do you have any kind of relationship with someone when they die? Of course. You have a relationship

of memory. Precious memories, dreams reflecting the significance of the relationship, and objects that link you to the person

who died (such as photos, souvenirs, etc.) are examples of some of the things that give testimony to a different form of a

continued relationship. This need of mourning involves allowing and encouraging yourself to pursue this relationship. But some people may try to take

your memories away. Trying to be helpful, they encourage you to take down all the photos of the person who died. They tell

you to keep busy or even to move out of your house. But in my experience, remembering the past makes hoping for the future

possible. Your future will become open to new experience only to the extent that you embrace the past. Need 4 - Developing a new self-identity Part of your self-identity comes from the relationships you

have with other people. When someone with whom you have a relationship dies, your self-identity, or the way you see yourself,

naturally changes. You may have gone from being a "wife" or "husband’ to being a "widow" or "widower." You may have gone from

being a "parent" to being a "bereaved parent." The way you define yourself and the way society defines you is changed. A death often requires you to

take on new roles that had been filled by the person who died. After all, someone still has to take out the garbage and buy

the groceries. You confront this changed identity every time you do something that used to be done by the person who died.

This can be very hard work and can leave you feeling very drained. You may occasionally feel child-like as you struggle with your changing identity. You may feel a

temporarily heightened dependence on others, as well as feelings of helplessness, frustration, inadequacy and fear. Many people discover that as

they work on this need, they ultimately discover some positive aspects of their changed self-identity. You may develop a renewed

confidence in yourself, for example. You may develop a more caring, kind and sensitive part of yourself. You may develop an

assertive part of your identity that empowers you to go on living even though you continue to feel a sense of loss. Need 5 - Searching for meaning When someone you love dies, you

naturally question the meaning and purpose of life. You probably will question your philosophy of life and explore religious

and spiritual values as you work on this need. You may discover yourself searching for meaning in your continued living as

you ask "How?" and "Why?" questions - How could God let this happen? Why did this happen now, in this way? The death reminds you of your

lack of control. It can leave you feeling powerless. The person who died was a part of you. This death means you mourn a loss not only outside of yourself,

but inside of yourself as well. At times, overwhelming sadness and loneliness may be your constant companions. You may feel

that when this person died, part of you died with him or her. And now you are faced with finding some meaning in going on

with your life, even though you may often feel empty. This death also calls for you to confront your own spirituality. You may doubt your faith and have

spiritual conflicts and questions racing through your head and heart. This is a normal part of your journey toward renewed

living. Need

6 - Receiving ongoing support from others The quality and quantity of understanding support will have a major influence on your capacity to

heal. You cannot - nor should you try to - do this alone. Drawing on the experiences and encouragement of friends, fellow

mourners or professional counselors is not a weakness but a healthy human need. And because mourning is a process that takes

place over time, this support must be available months and even years after the death of someone in your life. To be truly helpful, the people

in your support system must appreciate the impact this death has had on you. They must understand that in order to heal, you

must be allowed - even encouraged - to mourn long after the death. And they must encourage you to see mourning not as an enemy

to be vanquished, but as a necessity to be experienced as a result of having loved. Reconciling Your Grief You may have heard - indeed you may even believe - that your

grief journey’s end will come when you resolve or recover from your grief. But your journey will never end. People do

not "get over" grief. Reconciliation is a term I find more appropriate for integrating the new reality of moving forward in life, without

the physical presence of the person who died. With reconciliation comes a renewed sense of energy and confidence, an ability

to fully acknowledge the reality of the death, and a capacity to become reinvolved in the activities of living. In reconciliation, the sharp,

ever-present pain of grief gives rise to a renewed sense of meaning and purpose. Your feeling of loss will not completely

disappear, yet it will soften, and the intense pangs of grief will become less frequent. Hope for a continued life will emerge

as you are able to make commitments to the future. And realizing the person who died will never be forgotten, yet knowing

your life can move forward, will surface as your ability to heal. (Dr Wolfelt is an internationally acclaimed grief educator and director of the Center for Loss and Life Transition

in Fort Collins, CO. This article is an excerpt from his book, The Journey Through Grief.)

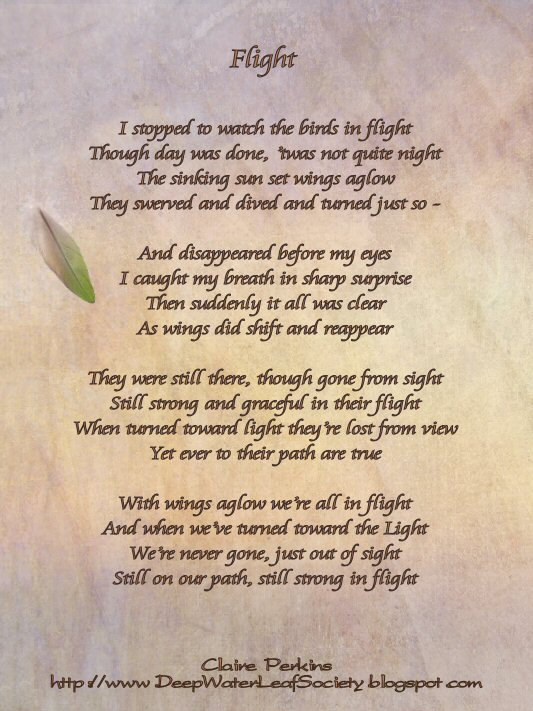

After reading this beautiful and uplifting poem by Claire Perkins, I made this animation and put

her words on a gentle background.

Helping Survivors Heal for family and friends of survivors

"Sometimes I

just want someone to be with me in silence,to sit quietly or go for a walk without any conversation.

Other times I need a listening ear or physical contact,a hug or

someone just to hold my hand.

I need to be aware of my own mental and emotional needs and seek to be nurtured in appropriate ways."

_______________________________________

'A time to grieve' C.Staudacher.

Helping A Survivor Heal

Historian Arnold Toynbee once wrote, "There are always two parties

to a death; the person who dies and the survivors who are bereaved." Unfortunately, many survivors of suicide suffer alone

and in silence. The silence that surrounds them often complicates the healing that comes from being encouraged to mourn. Because of the social stigma surrounding suicide, survivors feel the pain of the loss, yet may not know how, or where,

or if, they should express it. Yet, the only way to heal is to mourn. Just like other bereaved persons grieving the loss of

someone loved, suicide survivors need to talk, to cry, sometimes to scream, in order to heal. As a result of fear and misunderstanding, survivors of suicide deaths are often left with a feeling of abandonment

at a time when they desperately need unconditional support and understanding. Without a doubt, suicide survivors suffer in

a variety of ways: one, because they need to mourn the loss of someone who has died; two, because they have experienced a

sudden, typically unexpected traumatic death; and three, because they are often shunned by a society unwilling to enter into

the pain of their grief. How Can You Help?

A friend or family member has experienced the death of someone loved from suicide. You want to help,

but you are not sure how to go about it. This page will guide you in ways to turn your cares and concerns into positive action.

Accept The Intensity Of The Grief

Grief

following a suicide is always complex. Survivors don't "get over it." Instead, with support and understanding they can come

to reconcile themselves to its reality. Don't be surprised by the intensity of their feelings. Sometimes, when they least

suspect it, they may be overwhelmed by feelings of grief. Accept that survivors may be struggling with explosive emotions,

guilt, fear and shame, well beyond the limits experienced in other types of deaths. Be patient, compassionate and understanding.

Listen With Your Heart

Assisting

suicide survivors means you must break down the terribly costly silence. Helping begins with your ability to be an active

listener. Your physical presence and desire to listen without judgment are critical helping tools. Willingness to listen is

the best way to offer help to someone who needs to talk.

Thoughts and feelings inside

the survivor may be frightening and difficult to acknowledge. Don't worry so much about what you will say. Just concentrate

on the words that are being shared with you. Your friend may relate the

same story about the death over and over again. Listen attentively each time. Realize this repetition is part of your friend's

healing process. Simply listen and understand. And, remember, you don't have to have the answer. Avoid Simplistic Explanations and Clichés

Words, particularly clichés, can be extremely painful for a suicide survivor. Clichés are trite comments often intended

to diminish the loss by providing simple solutions to difficult realities. Comments like, "You are holding up so well," "Time

will heal all wounds," "Think of what you still have to be thankful for" or "You have to be strong for others" are not constructive.

Instead, they hurt and make a friend's journey through grief more difficult.

Be certain to avoid passing judgment or providing simplistic explanations of the suicide. Don't make the mistake

of saying the person who suicided was "out of his or her mind." Informing a survivor that someone they loved was "crazy or

insane" typically only complicates the situation. Suicide survivors need help in coming to their own search for understanding

of what has happened. In the end, their personal search for meaning and understanding of the death is what is really important.

Be Compassionate

Give your friend permission to express his or her feelings without fear of criticism. Learn from your friend. Don't

instruct or set explanations about how he or she should respond. Never say "I know just how you feel." You don't. Think about

your helping role as someone who "walks with," not "behind" or "in front of" the one who is bereaved.

Familiarize yourself with the wide spectrum of emotions that many survivors of suicide experience. Allow your friend

to experience all the hurt, sorrow and pain that he or she is feeling at the time. And recognize tears are a natural and appropriate

expression of the pain associated with the loss. Respect The Need To Grieve

Often ignored in their grief are the parents, brothers, sisters,

grandparents, aunts, uncles, spouses and children of persons who have suicided. Why? Because of the nature of the death, it

is sometimes kept a secret. If the death cannot be talked about openly, the wounds of grief will go unhealed.

As a caring friend, you may be the only one willing to be with the survivors. Your physical presence

and permissive listening create a foundation for the healing process. Allow the survivors to talk, but don't push them. Sometimes

you may get a cue to back off and wait. If you get a signal that this is what is needed, let them know you are ready to listen

if, and when, they want to share their thoughts and feelings. Understand The Uniqueness Of Suicide Grief

Keep in mind that the grief of suicide survivors is unique. No one will respond to the death of someone loved in

exactly the same way. While it may be possible to talk about similar phases shared by survivors, everyone is different and

shaped by experiences in his or her life.

Because the grief experience is unique, be patient. The process

of grief takes a long time, so allow your friend to process the grief at his or her own pace. Don't criticize what is inappropriate

behavior. Remember the death of someone to suicide is a shattering experience. As a result of this death, your friend's life

is under reconstruction. Be Aware Of Holidays And Anniversaries

Survivors of suicide may have a difficult time during special occasions

like holidays and anniversaries. These events emphasize the absence of the person who has died. Respect the pain as a natural

expression of the grief process. Learn from it. And, most importantly, never try to take the hurt away.

Use the name of the person who has died when talking to survivors. Hearing the name can be comforting and it confirms

that you have not forgotten this important person who was so much a part of their lives. Be Aware Of Support Groups

Support

groups are one of the best ways to help survivors of suicide. In a group, survivors can connect with other people who share

the commonality of the experience. They are allowed and encouraged to tell their stories as much, and as often, as they like.

You may be able to help survivors locate such a group. This practical effort on your part will be appreciated.

Respect Faith And Spirituality

If you allow them, a survivor will "teach you" about their feelings

regarding faith and spirituality. If faith is part of their lives, let them express it in ways that seem appropriate. If they

are mad at God, encourage them to talk about it. Remember, having anger at God speaks of having a relationship with God. Don't

be a judge, be a loving friend.

Survivors may also need to explore how religion may have complicated

their grief. They may have been taught that persons who take their own lives are doomed to hell. Your task is not to explain

theology, but to listen and learn. Whatever the situation, your presence and desire to listen without judging are critical

helping tools. Work Together As Helpers

Friends and family who experience the death of someone to suicide must no longer

suffer alone and in silence. As helpers, you need to join with other caring persons to provide support and acceptance for

survivors who need to grieve in healthy ways.

To experience grief is the result of having loved. Suicide survivors

must be guaranteed this necessity. While the above guidelines on this page will be helpful, it is important to recognize that

helping a suicide survivor heal will not be an easy task. You may have to give more concern, time and love than you ever knew

you had. But this effort will be more than worth it. ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Alan D. Wolfelt is a noted author, educator and practicing

thanatologist. He serves as Director of the Center for Loss and Life Transition in Fort Collins, Colorado and is on the faculty

at the University of Colorado Medical School in the Department of Family Medicine.

As a leading authority in the field of thanatology, Dr. Wolfelt is known internationally

for his outstanding work in the areas of adult and childhood grief. Among his publications are the books, Death and Grief;

A Guide For Clergy, Helping Children Cope With Grief and Interpersonal Skills Training: A Handbook for Funeral Home Staffs.

In addition, he is the editor of the "Children and Grief" department of Bereavement magazine and is a regular contributor

to the journal Thanatos.

From "Healing After the Suicide of a Loved One": One part of healing from the trauma of

a suicide is self-forgiveness. You need to accept that you might have done something differently, at some time, to have

made the person you lost a little happier without concluding that you are thus responsible for the suicide.

Please respect the copyright of my work.

I'm happy to share

it, but if

you'd like to use it, please

ask permission and credit the work to me, along with a link to this website.

Thanks

|

|

|